When reading a building facade, our eyes play across the surfaces and our mind analyses what we see in an attempt to identify balance and delight. Proportional symmetry in fenestration is a crucial part of how our subconscious mind forms an aesthetic judgement and therefore produces an aesthetic emotion. Although providing ample tutelage on how to balance window openings across a facade, a striking detail often overlooked in eighteenth-century pattern books is fenestration glazing, and glazing furniture. This is curious when we consider that the thickness of a glazing bar for instance is integral to a facade appearing dense and imposing or weightless and inviting. It was hardly the case that glazing was not considered of visual importance by the early eighteenth-century architect. Was its manufacture so controlled as to not necessitate illustrating? The method of illustrating windows on facades changed over the course of the century, and publications in the latter half of the eighteenth century include glazing bars on their buildings. By the early nineteenth century the incorporation of fenestration into illustrated facades appears commonplace.

Abraham Swan (A Collection of Designs in Architecture, 1757) includes glazing bars in his designs for interiors but not exteriors. Matthew Brettingham in his treatise on Holkham Hall (The Plans, Elevations, and Sections of Holkham Hall, 1773) does likewise. Batty Langley’s The Builder’s Jewel, 1741, exhibits many designs for window architraves and pediments but does not include any sashes or glazing bars. Colen Campbell’s Vitruvius Britannicus (in 3 vols., 1715, 1717, 1725) does not illustrate glazing bars on external facades, but George Richardson’s New Vitruvius Britannicus (in 2 vols., 1802, 1808) does.

Abraham Swan (1757) A Collection of Designs in Architecture, vol.2.

Matthew Brettingham (1773) The Plans, Elevations, and Sections of Holkham Hall.

Matthew Brettingham (1773) The Plans, Elevations, and Sections of Holkham Hall.

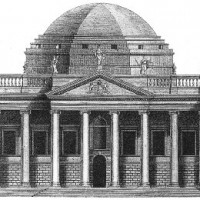

Robert and James Adam, New Assembly Room, Glasgow; from George Richardson (1802) New Vitruvius Britannicus, vol. 1.

Hawksmoor, et. al. (The Builders’ Dictionary, 1734) informed by a Mr. Leybourn, note several types of glass available, and report that ‘an English glass-maker went over to France on purpose to learn the French way of making glass; which he having attained to, came over again into England, and set up making of Crown Glass, and in the performance, outstripped the French his teachers’. The dictionary includes a price for crown glass; between £0.0s.6d and £0.0s.8d per square foot, and a price for ‘looking glass’ at a much higher rate of around £0.4s.0d per square foot. Interestingly, it also notes a type called ‘Jealous Glass’ costing around £0.0s.18d per square foot, which obscures visibility and is ‘commonly used in and about London, to put into the lower lights of sash-windows …to hinder people who pass by from seeing what is done in the room’.

The view of the front facade of Dr. Steeven’s Hospital, Dublin as illustrated above (Robert Pool and John Cash, Views of the most remarkable Public Buildings, Monuments and other Edifices in the City of Dublin, 1780) gives an altogether different impression to the photograph.

Early eighteenth-century glazing is composed of a thick glazing bar and a small pane of glass. Few buildings have retained their early fenestration but included in their number is Dr. Steevens’ Hospital, Dublin (designed by Thomas Burgh, c. 1717) where the heaviness of the glazing bars creates a sense of enclosed fortitude in the facade. Later in the century this style was replaced by the more delicate composition of light thin glazing bars, which were sometimes made of metal and veneered with timber.

Early eighteenth-century window on basement, Castletown House, Co. Kildare

The windows at Castletown House above basement level were refitted with sashes composed of a thinner glazing bar in the later eighteenth-century.

There were two distinct methods for making glass in the eighteenth century. The first, crown or spun glass, is made by spinning molten glass into a large disc shape, forming an undulating effect radiating from its centre. This disc was then cut into panes with the price diminishing as the pane neared the centre of the disc. The bulls-eye in the centre of the disc was then considered the cheapest of the panes, but is now in fact much sought after as a rare novelty.

An example of Crown glass

The second method, for making cylinder glass or ‘looking glass’, necessitated the forming of a cylindrical shape and then elongating the cylinder by swinging the form into a deep trench. Whilst molten, this cylinder was cut and flattened out. This glass is easily identified due to the presence of bubbles in the composition which were circular in the cylinder but became elongated ovals when the cylinder was flattened out. This type of glass was more expensive than crown glass due to the viewing clarity it afforded the end user.

Cylinder glass with two distinct oval inclusions.

Varying colours clearly evident in eighteenth-century glass is due to the irregular ratios in the composition of materials used in its manufacture, as illustrated in the basement window above. However, Hawksmoor, et. al. attribute the varying colours to the areas in which they were manufactured; Radcliff glass for instance was a sky blue colour, Lambeth Crown glass a green colour, and German glass either a green or white colour.

It is regrettable that much historic glass has been removed from many historic properties in favour of modern materials whose lifespan comes nowhere close to that of what it replaced.

_______________

Posted on 25-05-16

Citation; McKenna, M. (2016) Know Your Glazing. Available at www.georgianireland.com (Accessed dd/mm/yyyy)